Maybe one of the most important sessions at the recent 22nd International AIDS Conference AIDS 2018 held in Amsterdam was the session, which raised the question why we still fail in responding to the epidemic among people who inject drugs. Participants of the session were able to consider this problem from the different points of view: science, law enforcement and community of people who use drugs.

Maybe one of the most important sessions at the recent 22nd International AIDS Conference AIDS 2018 held in Amsterdam was the session, which raised the question why we still fail in responding to the epidemic among people who inject drugs. Participants of the session were able to consider this problem from the different points of view: science, law enforcement and community of people who use drugs.

Methadone is good for police

For over 20 years, Professor Nick Crofts from the University of Melbourne has been working to engage police in HIV response. He considers that decriminalisation is an absolute necessity to resolve the problem.

“We fail responding to the epidemic because we have failed to enlist police as partners in the response to HIV,” he says. “Changing the situation, first of all, requires changing the role of police, which will, in turn, help bringing the marginalized communities back to the society.”

In Australia, Professor Crofts and his allies were able to convince the police that such harm reduction programmes as methadone therapy and syringe exchange may benefit police as well as the rest of the community.

“We still have not introduced harm reduction courses in police academies, have not adequately educated police and have not fostered the role of peer educators, which is important not only in the traditional environment of activists, but also in such specific group as future or current police officers. Police officers may listen only to other police officers,” says Nick Crofts with a smile.

HIV for culture change

It is essential to find police officers who support the idea of harm reduction and educate them so that they can then educate their colleagues in relevant agencies.

It is essential to find police officers who support the idea of harm reduction and educate them so that they can then educate their colleagues in relevant agencies.

“Find at least one or two individuals who want to do something different! Find them and give them your support!” exclaims Professor Crofts.

HIV may be a starting point to change the culture of the police. For a start, we need to engage the police, hold joint workshops with people from civil society and police, foster gender diversity in the police (to recruit more female police officers) and, finally, include harm reduction into the programme of police academies.

However, the Professor points out that it may sound pie in the sky talking about police in some countries.

“A third of them understand harm reduction, a third can understand and another third will never understand. Our goal is to find those people who understand or can understand it and work with them until they outnumber those who will never understand harm reduction,” he says.

“Narcotic ration” for Russia

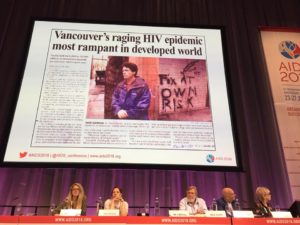

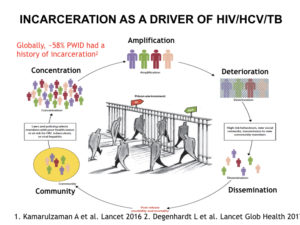

Dr. M-J Milloy, the epidemiologist from Vancouver, tells about an interesting case, which occurred in his city back in the 1990s. Back then, there was already a large needle and syringe exchange programme in Vancouver and methadone was available. The epidemic among people who use drugs had successfully been curbed, but suddenly there was an unexpected outbreak of new HIV cases. How could it happen in a city with a well-developed harm reduction programme? It was explained with the fact that people could not access the necessary services when they were incarcerated.

Epidemiologists found out that incarceration was one of the key factors increasing the risk of HIV acquisition and one in five new HIV cases in Vancouver was a result of incarceration.

At the same time, experts estimate that in Russia every hour ten people are infected with HIV, while tuberculosis is the main reason of mortality among those who live with HIV. Most of them are people who inject drugs. The country does not offer evidence-based treatment to people who use drugs, i.e. there is no methadone, which, according to a recent statement from the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, is a “narcotic ration.”