By Rico Gustav, Executive Director of Global Network of People Living with HIV

By Rico Gustav, Executive Director of Global Network of People Living with HIV

COVID-19 has exposed how weak our health systems are and how little attention we have paid to global health security. Thailand, a country that has been well known for its public health systems and hosts one of the best public health universities, has declared within 4 weeks of the beginning of the spread of COVID 19 that they “are unable to stop the spread” of COVID-19.

The story is not that different in the Netherlands, where local doctors serve as the first entry point to the entire health system. I live in a small city in the Netherlands where the local doctor is being overwhelmed by the number of people wanting to check if they have COVID-19. The combination of mass panic and the fact that the seasonal flu is going around is basically crippling the entire healthcare system.

COVID-19 has made it clear that not only is our traditional health system not ready, neither is our global economic system. The mass panic is not something we should underestimate. Last week, a friend asked me whether they should start hoarding toilet paper, as if this is an epidemic of diarrhea. Non-prescription medicines are running out in our local supermarkets and empty shelves are everywhere. Financial sectors are going mad with everyone buying gold and leaving market stocks free falling into the abyss. The disruption in the global chain supply reminded us of our interconnected universe, despite government leaders often denying the need to act as a united world.

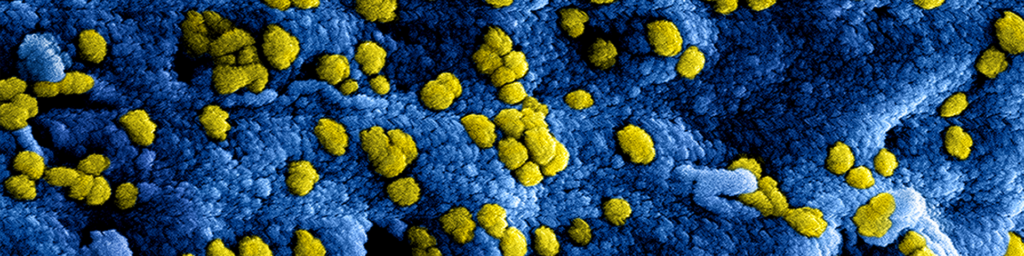

For us, people living with HIV, we are relying on our ARV medications to be able to stay healthy. Compared with the general population, people with compromised immunity are at higher risk of contracting the new coronavirus and developing more serious COVID-19 illness or dying. However, on ARVs and with a suppressed viral load and higher CD4 count, people living with HIV do not all have compromised immune systems and are at no greater risk.

The British HIV Association has stated that for now, there is no evidence to determine whether people with HIV are at greater risk of COVID-19 acquisition or severe disease. The main mortality risk factors to date are older age and co-morbidities, including renal disease and diabetes. Some groups with relative immune suppression, such as the very young and pregnant women, do not appear to be at higher risk of complications, although numbers are very small. They also caution that there is a possibility of atypical presentations in clients who are immunocompromised.

Beyond our personal risk of increased morbidity, there is a growing concern that a global disruption to chain supply may also influence the supply of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs), the basic ingredients for any medications, including our ARVs which is mainly produced in China. The generic ARVs are also mainly produced in India. This means that our entire ARV supplies depending on two countries sitting in the region most affected by COVID-19. While the Global Fund and UNAIDS have been working hard to monitor the impact of COVID-19 to ARV production and distribution, we, as a global health community, need to also pay attention to the early signs of any issue to chain supply management of any medications. The challenge at the moment is that the story of COVID-19 is still unfolding and estimating the long term impact is a daunting task.

The pressure COVID-19 has put on the health system clearly illustrates the need to evolve the traditional health system. To ensure that the health system is able to respond to an outbreak like this, the engagement of community response to improve health outcomes and maintaining health security become crucial. When healthcare centers become fertile grounds for transmission, the role of the community to act as a bridge between people in their own environment and health centers, becomes critical. The role of community in this context also becomes crucial in improving early detection and quick response, because it can reach those who are unreachable to a passive-health system.

We have experience in the HIV sector of using community systems to deliver client-centered care, while reducing the burden on health care systems. In many places, what is called Differentiated Service Delivery is implemented, where people do not need to go to their health facility to collect their ARVs, easing pressure on health care workers, and allowing more time and attention on people who need it, with proven similar health outcomes. Now more than ever, we need to roll out these models to ease the burden on the health care system, but also so that it becomes easier for people living with HIV to access their medication. Studies have also shown that during disease outbreaks such as Ebola, people are less likely to access other health services, as illustrated in West Africa where there was a 50% reduction in access to healthcare services, which increased malaria, HIV, and tuberculosis mortality rates, illustrating the need for community responses to provide healthcare services in the community, when people are afraid to access health care facilities.

While COVID-19, like HIV, does not discriminate against its target of infections, it exaggerates inequality that we have in the society. In countries where healthcare is highly privatized (like my own, Indonesia), poorer and marginalized people are more discouraged to go to healthcare centers to get tested. Even when people have symptoms that they know might be indications of COVID-19 infections, they just have to bet that it is not. Because if it is, the cost of the hospitals might actually be the thing that affects them most. This should make the world realise, that because health is a public matter, healthcare should be public and not left to the forces of the private sector. And because health is priceless, medications should be free at point of care.

While it is difficult to be helpful in situation where none of us are familiar with, as groups and networks of health activists working on HIV, here are some of the things we may be able to do:

- Stay safe: follow latest information about COVID-19 and always check the accuracy of the information by verifying the source.

- Check your local and national ARV supply and chain management: Ensure that you understand where potential bottlenecks are, what are the scenarios for solutions and how your network can help. Do similar things on any other health-commodities in AIDS response: needles and syringes, condoms, etc.

- Ask your Ministry of Health to instruct ARV access points to adhere to WHO Guidelines for Differentiated Service and to provide longer term (3 months) supplies for all PLHIV on ARV treatment, so that it lessens the frequency of going to healthcare centers.

- Work with local key population groups (LGBTI people, sex workers, prisoners and people who use drugs) who may be afraid to access health care services because of stigma, discrimination, to ensure that they have access to health care and appropriate services.

- Discuss with other community and civil society groups and create a small working group on COVID-19 and HIV that can act as an information center and distribution. The group should monitor latest news on COVID-19 and relay the accurate information to other civil society groups.

- Continue to engage with the government and other actors in HIV response to monitor the progress of COVID-19 and to prepare for different scenarios of pandemic.

- Monitor how your government’s response to COVID-19 and make sure that human rights continue to be promoted and protected. While quarantine is a public health tool, it is not an excuse to violate human rights and people’s right to dignity.

People living with HIV are resilient. We have worked together tirelessly for quality of life and better health outcomes and will continue to do so.

Source – GNPPLUS.